The Arcadian Times-Transcript

This is a place that I post some of my more manic ramblings and interest items.Imagery is very important to me so I sometimes tend to let pictures speak for themselves.While most of the information here deals with the people and history of greater Atlantic Canada, Oak Island seems to take the forefront due to an ancestral connection. The Canadian Military's mission to Afghanistan is also commented on here. You are bound to find worldwide items of interest as well.

Saturday, June 11, 2005

Friday, June 10, 2005

Where in the world is Ancient Norumbega?

| Search |

| Palimpsest: 1. a piece of writing material or manuscript on which the original writing has been erased to make room for other writing. 2. a place, etc., showing layers of history, etc. (The Oxford Dictionary and Thesaurus, 1996, pg. 1075). |

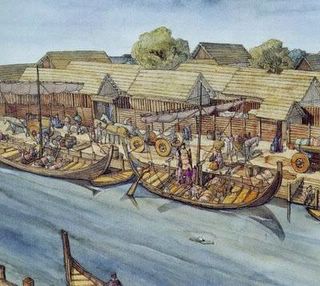

Recent writing by historians and archaeologists (Brasser, Bourque and Prins) on late ceramic and early contact period ethnohistory (1400 - 1620) splits Maine Native American communities into two cultures. Semisedentary horticulturists are postulated as living west of the Saco River (or alternatively the Kennebec River). Wandering seminomadic hunting and fishing bands of Etchemins are postulated as living east of these rivers without any permanent village sites, and having a different language and lifestyle than those to the west. This theory is based on French sources, especially the twenty explorations of Champlain (1604 -1605) and Father P. Biard.

Contradicting this theory are the experiences and written and oral history of English explorers and settlers (1605 - 1763) and Maine historians writing in the 19th century, especially William Williamson (History of Maine, 1832). Of particular importance is the narration of the confederacy of Mawooshen derived from George Weymouth's 1605 exploration of the Pemaquid - St. Georges River region. Five Native Americans kidnapped by Weymouth and brought to England recounted the only existent Native American historical description of Mawooshen to Fernando Gorges, which Samuel Purchas printed in 1625 (Purchas, his pilgrims). Located between Massachusetts Bay and Schoodic Point, Maine, the confederacy consisted of 20 or more tidewater villages stretching east from the Saco River to Schoodic Point, with numerous affiliated tribal communities to the west as far as Plymouth, MA and Cape Cod Bay.

Further complicating this controversy are the many theories about the meaning, significance and location of Norumbega noted on many 16th century or early 17th century maps as either a place name for a community on the Penobscot River, or denoted as the general region of the central New England coast. Further adding to this controversy and of most interest to Maine residents is the deletion of reference in recent writings on Maine's ethnohistoric past to the community of the Wawenoc Indians of the central Maine coast so prominently featured in the writings of William Williamson and other Maine historians.

Norumbega Reconsidered and the Wawenoc Diaspora explores these conflicting views of Maine's ethnohistoric past and includes extensive excerpts from and commentaries by Snow, Bourque, and Sewall about recent as well as 19th century writings on these subjects.

Our journey into the past history of Native Americans on the central Maine coast begins with the first trickle of settlers into Davistown in the 1770s then travels back in time, encountering more than just a simple English colonial presence in ancient Pemaquid after 1620. The lack of written records before that date complicate and obscure the documentation of pre-1620 European visitors and settlers in coastal Maine. It does not, however, erase the entrenched oral tradition of a lingering memory of English, Spanish, French, Basque and Native American visitors in ancient Pemaquid and elsewhere in the maritime peninsula. Numerous Maine historians of 18th and 19th centuries narrate these oral traditions. The English presence in the ancient Pemaquid region began far earlier than 1620 and pre-dates the written records that document the great English migration to coastal New England which began in 1630. The presence of a Basque community of seasonal fishermen and traders at Pemaquid in the early to mid-16th century lingers unconfirmed in some older Maine histories (Woodbury etc.)

The process of peeling back each layer of the history of central coastal Maine leads to a Native American presence that becomes more dominant the further back in time Maine history is explored. The ancient Pemaquid of pre-1620 English visitors was in fact a polyglot community of Native Americans, European traders from many nations and English fishermen, explorers and settlers. Over a century of relatively peaceful trade in the Pemaquid region between Europeans and Native Americans preceded the Indian Wars of 1676. The widespread intertribal warfare over the fur trade (1607 - 1617) may have been a brief interregnum of violence before the catastrophe of the great pandemic swept away most of the Native American communities on the Maine and New England coast west of Schoodic Point. Those Native Americans who survived to trade with the English after 1620 at Pemaquid and other coastal locations were the remnants of a series of robust tidewater Native American communities that dominated the New England coastline before 1600. These survivors were joined by an influx of Etchemins (Passamaquoddy, Maliseet) from the east and north -- an influx that continues to influence our interpretation of coastal Maine ethnohistory to this day. English fishing and trading stations and undocumented settlements at Pemaquid, Monhegan and elsewhere after 1550 were the second footholds of what was already an invasion of Europeans -- Spanish, French, Dutch, Basque -- in the Canadian maritimes and St. Lawrence River basin. The ethnohistory of the Native American communities of coastal Maine prior to 1600 was radically altered by this European invasion.

Flourishing for centuries, the ancient Pemaquid of Euroamerican fishermen, traders and explorers was "Pemquit," among the most important and accessible of the Native American settlements and summer trading stations described by the five Native Americans captured by George Weymouth in 1605 in Samuel Purchas' Narrative of Mavooshem (1626). There are very few historical descriptions derived from Native American narrators; Frank Speck is perhaps the most prominent of early 20th century writers to recount the oral traditions and family histories of one of the principal tribes of Maine, described in Williamson's History of Maine, the Penobscot Indians. The description of the confederacy of Mawooshen in Purchas stands alone; there is no other specific written Native American record of these Native American communities, but their archaeological, geographical and linguistic traces are a ubiquitous presence in the tidewater communities downstream from the Davistown Plantation. In contrast, a vast Euroamerican historical literature -- both modern and antiquarian -- details their presence in oral traditions that describe the lingering memories of the first European settlers of these communities. The observations of English explorers and settlers after 1600, much more so than the French sources, memorialize their fading presence, which ended in violence, bloodshed, bounties and oblivion for Native Americans living west and south of the Penobscot River. Few Native American residents west of the Penobscot River survived the European onslaught. The commemoration of Samoset, one of the few members of the Wawenoc community to survive the great pandemic of 1617, is a vestige of our nearly subconscious awareness of these now extinct communities. The combined processes of the physical eradication of Native American villages and Euroamerican construction of new villages, new communities and new historical perspectives - the advent of a new culture - continues the pattern of the layering of one historical palimpsest upon another. This process has gradually obliterated our memory of the many Native American communities which preceded us and are, in many cases, no longer represented by survivors who can defend and renew their ancestral heritage. The reconnoitering of history means peeling back contemporary revisionists theories of what we now think about Native American presence in coastal Maine before and during the first colonial dominion. This broad sweep of revisionist theory has removed from our recent written history acknowledgment of and respect for the Wawenoc community of the central Maine Coast, now considered too unimportant -- too much of a bother -- to document, to remember. Listening to the narratives and tales of the older historians is the first step in reconsidering and remembering this past. This process of remembering discloses a culture that, in the case of the Wawenocs, commingled briefly with its European invaders before disappearing with no descendants. The history of ancient Pemaquid is a reminder that our collective remembrance of the past must include not just our European ancestors or the traditions of the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy and Maliseets of the historic era but the tribal communities that did not survive the European conquest of North America.

cont

Thursday, June 09, 2005

The Rock Hewn Churches of Lalibela, Ethiopia

Church of St George,Lalibela, Ethiopia

From http://www.selamta.net

The Legend of Lalibela.

Ever since the first European to describe the rock churches of Lalibela, Francisco Alvarez, came to this holy city between 1521 and 1525, travellers have tried to put into words their experiences. Praising it as a “New Jerusalem”, a “New Golgotha”, the “Christian Citadel in the Mountains of Wondrous Ethiopia”. The inhabitants of the monastic township of Roha-Lalibela in Lasta, province of Wollo, dwelling in two storeyed circular huts with dry stonewalls, are unable to believe that the rock churches are entirely made by man. They ascribe their creation to one of the last kings of the Zagwe dynasty, Lalibela, who reigned about 1200 A.D.The Zagwe dynasty had come to power in the eleventh century, one hundred years after Queen Judith, a ferocious woman warrior had led her tribes up from the Semyen mountains to destroy Axum, the capital of the ancient Ethiopian empire in the north.The charming Ethiopian folklore pictures telling the story of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, which are sold in Addis Ababa, give a popular version of how not only the dynasty of ancient Axum (and present day Ethiopia) descended from King Solomon, but also the medieval Zagwe dynasty. The Queen of Sheba gave birth to Menelik, who became the first King of Ethiopia. But the handmaid of the Queen, too, gave birth to a son whose father was King Solomon, and her son was the ancestor of the Zagwe dynasty.The Zagwe kings ruled until the thirteenth century, when a famous priest, Tekla Haymanot, persuaded them to abdicate in favour of a descendant of the old Axumite Solomonic dynasty.

However, according to legend before the throne of Ethiopia was restored to its rightful rulers, upon command of God and with the help of angels, Lalibela’s pious zeal converted the royal residence of the Zagwe in the town of Roha in to a prayer of stone.The Ethiopian Church later canonized him and changed the name of Roha to Lalibela. Roha, the centre of worldly might, became Lalibela the holy city; pilgrims to Lalibela shared the same blessings as pilgrims to Jerusalem, while the focus of political power drifted to the south, to the region of Shoa. Legends flower in Lalibela, and it is also according to legend that Lalibela grew up in Roha, where his brother was king. It is said that bees prophesied his future greatness, social advance and coming riches. The king, made jealous by these prophecies about his brother tried to poison him, but the poison merely cast Lalibela into a death like sleep for three days. During these three days an angel carried his soul to heaven to show him the churches which he was to build. Returned once more to earth he withdrew into the wilderness then took a wife upon God’s command with the name of Maskal Kebra (Exalted Cross) and flew with an angel to Jerusalem. Christ himself ordered the king to abdicate in favour of Lalibela. Anointed king under the throne name Gare Maskal (Servant of the Cross) Lalibela, living himself an even more severe monastic life than before, carried out the construction of the churches. Angels worked side by side with the stone masons, and within twenty four years the entire work was completed.

cont. in comments

Wednesday, June 08, 2005

Quercus cerris

Turkey Oak

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

| Turkey Oak Conservation status: Secure | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey Oak foliage | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Quercus cerris L. |

The Turkey Oak (Quercus cerris) is an oak native to southern Europe and Asia Minor. It is the type species of Quercus sect. Cerris, a section of the genus characterised by shoot buds surrounded by soft bristles, bristle-tipped leaf lobes, and acorns that usually mature in 18 months.

contJames Bruce

Enc. Brittanica

James Bruce esq (December 14, 1730 - April 27, 1794) was a Scottish traveller and travel writer.

He was born at the family seat of Kinnaird, Perthshire, and educated at Harrow School and Edinburgh University, and began to study for the bar; but his marriage to the daughter of a wine merchant resulted in his entering that business. His wife died in October 1754, within nine months of marriage, and Bruce thereafter travelled in Portugal and Spain. The examination of oriental MSS. at the Escurial led him to the study of Arabic and Geez and determined his future career. In 1758 his father's death placed him in possession of the estate of Kinnaird. On the outbreak of war with Spain in 1762 he submitted to the British government a plan for an attack on Ferrol. His suggestion was not adopted, but it led to his selection by the 2nd Earl of Halifax for the post of British consul at Algiers, with a commission to study the ancient ruins in that country, in which interest had been excited by the descriptions sent home by Thomas Shaw I (1694-1751), who was consular chaplain at Algiers. Having spent six months in Italy studying antiquities, Bruce reached Algiers in March 1763. The whole of his time was taken up with his consular duties at the piratical court of the dey, and he was kept without the assistance promised. But in August 1765, a successor in the consulate having arrived, Bruce began his exploration of the Roman ruins in Barbary. Having examined many ruins in eastern Algeria, he travelled by land from Tunis to Tripoli, and at Ptolemeta took passage for Candia; but was shipwrecked near Bengazi and had to swim ashore. He eventually reached Crete, and sailing thence to Sidon, travelled through Syria, visiting Palmyra and Baalbek. Throughout his journeyings in Barbary and the Levant, Bruce made careful drawings of the many ruins he examined. He also acquired a sufficient knowledge of medicine to enable him to pass in the East as a physician.

How Glooskap is making Arrows, and preparing for a Great Battle

Photo PANS

How Glooskap is making Arrows, and preparing for a Great Battle. The Twilight of the Indian Gods.

(Passamaquoddy.)

“Is Glooskap living yet?” “Yes, far away; no one knows where. Some say he sailed away in his stone canoe beyond the sea, to the east, but he will return in it one day; others, that he went to the west. One story tells that while he was alive those who went to him and found him could have their wishes given to them. But there is a story that if one travels long, and is not afraid, he may still find the great sagamore ( sogmo). Yes. He lives in a very great, a very long wigwam. He always making arrows. One side of the lodge is full of arrows now. They so thick as that. When it is all quite full, he will come forth and make war. He never allows any one to enter the wigwam while he is making these arrows.”

cont

Tuesday, June 07, 2005

Kluskap's Advice

Photo Dr Helen Creighton

Recording Mi'kmaq speech. Chief William Paul, Martin Sack, Ben Knockwood, and John Knockwood.

Chief Paul Shunenacadie, NS,1948

Glooscap’s Advice

Well now about this great Glooscap, what he had told to his people before he left – before he left – to this province, after he had teached them of good many different things, what’s to be done to themselves to please the others and then he told them,

“My dear childrens, now that I’m goin’ to north, and I’m goin’ to fix your homes because your home is distroubled here. Your home is distroubled. You’re now be living with white people which now they will deal with gold and silver, and years to come you will deal with the same thing.” But the Indians then didn’t know the colour of the gold nor silver, but they had known the name of the two different things. “Well now then, I am going leave after I’ve shown you everything that I want to show you. Now then your home will be taken, you all will think that people which are you going to live with them. But I am going to build your home way up north where nobody else can come and there it’ll be so good, and it’ll be mountains of gold that will be surrounded by your homes and it’s nobody can get there but yourselfs, but in years to come you will formerly think – you will formerly think – our province is all taken by those pale faces, but that will not be so. I will come and see the fair play, and I will come to see how that you will hold your homes and your province, cause the province is yours. It is nobody can prevail my words. And it’s therefore, and all the things that he had reference to the growth of the people, it all come so exact, so truly, but this here, by coming back, it never had arrived yet, but we are expecting it. No doubt we certainly do believe that he will come and see everything according to the truth, and so therefore, now the peoples had reached from here to the Klondike, and they had gone on them mountains and canyons which they had discovered a lot of gold. Nuggets.

Chief William Paul, Shubenacadie.

MG 1 2806 # 8 (Helen Creighton)

AC 2141

Monday, June 06, 2005

How Glooskap made the Elves and Fairies

From Algonquin Tales

How Glooskap made the Elves and Fairies, and then Man of an Ash Tree, and last of all, Beasts, and of his Coming at the Last Day.

(Passamaquoddy.)

Glooskap came first of all into this country, into Nova Scotia, Maine, Canada, into the land of the Wabanaki, next to sunrise. There were no Indians here then (only wild Indians very far to the west).

First born were the Mikumwess, the Oonabgemessuk, the small Elves, little men, dwellers in rocks.

And in this way he made Man: He took his bow and arrows and shot at trees, the basket-trees, the Ash. Then Indians came out of the bark of the Ash-trees. And then the Mikumwees said ... called tree-man.... [Footnote: The relater, an old woman, was quite unintelligible at this point.]

Glooskap made all the animals. He made them at first very large. Then he said to Moose, the great Moose who was as tall as Ketawkqu's, [Footnote: A giant, high as the tallest pines, or as the clouds.] “What would you do should you see an Indian coming?” Moose replied, “I would tear down the trees on him.” Then Glooskap saw that the Moose was too strong, and made him smaller, so that Indians could kill him.

cont

Thunder Stories

THUNDER STORIES

Of the Girl who married Mount Katahdin, and how all the Indians brought about their own Ruin.

(Penobscot.)

Of the old time. There was once an Indian girl gathering blueberries on Mount Katahdin. And, being lonely, she said, “I would that I had a husband!” And seeing the great mountain in all its glory rising on high, with the red sunlight on the top, she added, “I wish Katahdin were a man, and would marry me!”

All this she was heard to say ere she went onward and up the mountain, but for three years she was never seen again. Then she reappeared, bearing a babe, a beautiful child, but his little eyebrows were of stone. For the Spirit of the Mountain had taken her to himself; and when she greatly desired to return to her own people, he told her to go in peace, but forbade her to tell any man who had married her.

cont

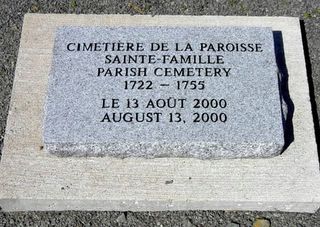

THE "GENERAL RETURN" OF 1767

Deportation Cross, Horton

THE "GENERAL RETURN" OF 1767

From Ed Coleman's Outdoor Page, orig, pub. Hants Journal

In a paper read before the Nova Scotia Historical Society in 1888, D. Allison called it one of the "most important documents" ever prepared on the history of early Nova Scotia. The document he referred to is the "General Return of the Several Townships in the province." In effect, this was a form of census and its value lies in it being prepared in 1767, just over a decade after expulsion of the Acadians and less than a decade after arrival of the Planters.

The years immediately following the expulsion of the Acadians was "one of the most formative epochs" in Nova Scotia history, Allison writes. The survey or general return for this period is important, he says, for the light it shed on those years, supplying "valuable information respecting the (Planters)" and "some light on the interesting question of Acadian repatriation."

cont

The Giant Magicians

The Giant Magicians

from Alkonquin tales

"There was once a man and his wife who lived by the sea, far away from other people. They had many children, and they were very poor. One day this couple were in their canoe, far from land. There came up a dense fog; they were quite lost.

They heard a noise as of paddles and voices. It drew nearer. They saw dimly a monstrous canoe filled with giants, who greeted the little folk like friends. “Uch keen, tahmee wejeaok?” “My little brother,” said the leader, “where are you going?” “I am lost in the fog,” said the poor Indian, very sadly. “Ah, come with us to our camp,” said the giant, who seemed to be a good fellow, if there ever was one. “Truly, ye will be well treated, my small friends, for my father is the chief; so be of good cheer!” And they, being much amazed at this gentleness, sat still in awe, while two of the giants, each putting a tip of his paddle under their bark, lifted it up and put it into their own, as if it had been a chip. And truly the giants seemed to be as much pleased with the little folk as a boy would be who had found a flying squirrel. [Footnote: A story like this of giants in a canoe would very naturally originate about the Bay of Fundy, where, in the dense and frequent fogs, all objects assume greatly exaggerated apparent dimensions. One often beholds there, on the shore, “men as trees walking.”]

cont

THE MASONIC STONE OF 1606

THE MASONIC STONE OF 1606

Friends,

This is an excerpt from an article written by Nova Scotia Grand Historian, Bro. Reginald V. Harris. A more detailed article, by the same author, appeared in the October 1924 issue of The Builder Magazine

| Quote: |

| The reader will recall that in 1605 Champlain, the French explorer, established the settlement of Port Royal on the west side of Annapolis Basin. This settlement was the predecessor of the more noted Port Royal and Annapolis Royal, built some miles to the northward, the scene of many sieges and history making events, including the organization of the first Masonic lodge on Canadian soil. On this first site was discovered in 1827, what some Masonic students and historians have regarded as the earliest trace of the existence of Freemasonry on this continent, namely certain marks on a stone found on the site of this early settlement. |

Isle Haute

From Ed Coleman's Outdoor Page, orig, pub. Hants Journal

The legends of Isle Haute reach back for centuries and have attracted many people to its shores. The island, like countless others, has been linked to treasure buried by Captain Kidd. One of the island’s most exciting episodes concerns a possible pirate treasure found by a popular historian and treasure hunter from down the coast in New England, Edward Rowe Snow.

In one of his many books Snow wrote that pirate Edward (Ned) Low “eventually became more fiendish in his captures at sea than any other pirate.” Snow wrote that Low’s travels eventually took him into the Bay of Fundy, and legend has it that while ashore on Isle Haute he beheaded an unruly crewmember. A handyman named Dave Spicer, who helped out at the lighthouse, claimed to have seen a headless ghost on multiple occasions. Another version of the headless ghost story claims that the island moves once every seven years. If you’re on the island at midnight when it moves, a “flaming headless ghost” can be seen, the story goes.

cont

Jerome

Friends,

The following is an account of the legend of Jerome, found marooned upon the Fundy shore of Nova Scotia.

| Quote: |

| It was early morning of September 8, 1863. A Sandy Cove fisherman gathering rock weed along the shore noticed a dark figure along side a big rock on Bay of Fundy beach. As the fisherman got closer he saw the huddled form of a man. Both legs had been amputated just above the knees and beside him was a jug of water and a tin of biscuits. His legs had, obviously, been amputated by a skilled surgeon and the stumps were only partially healed and bandaged. The man was also suffering from cold and exposure. The fisherman recalled a ship the day before passing back and forth a half mile off shore in St. Mary's Bay. It was surmised the man must have been brought in from the ship after dark and left on shore. |

Kluskap Legends

How Glooskap went to England and France, and was the first to make America known to the Europeans.

There was an Indian woman: she was a Woodchuck (Mon-in-kwess, P.). She had lost a boy; she always thought of him. Once there came to her a strange boy; he called her mother.

He had a pipe with which he could call all the animals. He said, “Mother, if you let any one have this pipe we shall starve.”

“Where did you get it?”

“A stranger gave it to me.”

One day the boy was making a canoe. The woman took the pipe and blew it. There came a deer and a qwah-beet,—a beaver. They came running; the deer came first, the beaver next. The beaver had a stick in his mouth; he gave it to her, and said, “Whenever you wish to kill anything, though it were half a mile off, point this stick at it.” She pointed it at the deer; it fell dead.

The boy was Glooskap. He was building a stone canoe. Every morning he went forth, and was gone all day. He worked a year at it. The mother had killed many animals. When the great canoe was finished he took his (adopted) mother to see it. He said that he would make sails for it. She asked him, “Of what will you make them?” He answered, “Of leaves.” She replied, “Let the leaves alone. I have something better.” She had many buffalo skins already tanned, and said, “Take as many as you need.”

He took his pipe. He piped for moose; he piped for elk and for bear: they came. He pointed his stick at them: they were slain. He dried their meat, and so provisioned his great canoe. To carry water he killed many seals; he filled their bladders with water.

So they sailed across the sea. This was before the white people had ever heard of America. The white men did not discover this country first at all. Glooskap discovered England, and told them about it. He got to London. The people had never seen a canoe before. They came flocking down to look at it.

The Woodchuck had lost her boy. This boy it was, who first discovered America (England?). This boy could walk on the water and fly up to the sky. [Footnote: This tale was taken down in very strange and confused English. The first part is in my notes almost unintelligible.] He took his mother to England. They offered him a large ship for his stone canoe. He refused it. He feared lest the ship should burn. They offered him servants. He refused them. They gave him presents which almost overloaded the canoe. They gave him an anchor and an English flag.

He and his mother went to France. The French people fired cannon at him till the afternoon. They could not hurt the stone canoe. In the night Glooskap drew all their men-of-war ashore. Next morning the French saw this. They said, “Who did this?” He answered, “I did it.”

They took him prisoner. They put him into a great cannon and fired it off. They looked into the cannon, and there he sat smoking his stone pipe, knocking the ashes out.

The king heard how they had treated him. He said it was wrong. He who could do such deeds must be a great man. He sent for Glooskap, who replied, “I do not want to see your king. I came to this country to have my mother baptized as a Catholic.” They sent boats, they sent a coach; he was taken to the king, who put many questions to him.

He wished to have his mother christened. It was done. They called her Molly. [Footnote: The Indians pronounce the word Marie Mahli or Molly. Mahlinskwess, “Miss Molly,” sounds like Mon-in-kwess, a woodchuck. Hence this very poor pun.] Therefore to this day all woodchucks are called Molly. They went down to the shore; to please the king Glooskap drew all the ships into the sea again. So the king gave him what he wanted, and he returned home. Since that time white men have come to America.

* * * * *

This is an old Eskimo tale, greatly modernized and altered. The Eskimo believe in a kind of sorcerers or spirits, who have instruments which they merely point at people or animals, to kill them. I think that the Indian who told me this story (P.) was aware of its feebleness, and was ashamed to attribute such nonsense to Glooskap, and therefore made the hero an Indian named Woodchuck. But among Mr. Rand's Micmac tales it figures as a later tribute to the memory of the great hero.

One version of this story was given to me by Tomah Josephs, another by Mrs. W. Wallace Brown. In the latter Glooskap's canoe is a great ship, with all kinds of birds for sailors. In the Shawnee legend of the Celestial Sisters (Hiawatha Legends), a youth who goes to the sky must take with him one of every kind of bird. This indicates that the Glooskap voyage meant a trip to heaven.

The Sacred Geometry of Acadia

An extract of The Sacred Geometry as detailed by John Coleman.

Observations by Mr Coleman and others provide insight into the strange placement of stele and other markers throughout the geography of Acadia.http://www.vortexmaps.com/novascotia/

Mysterious Trees of Oak Island

Oak Island Nova Scotia.

I have sent this image to regional botanists http://www.oakislandtreasure.co.uk/